Beyond the Med – Jew’s harp in an unfamiliar corner of Spain

In the far northwest of Spain lies Galicia.

By Ånon Egeland

Translated by Lucy Moffatt

The region is probably best known for the pilgrimage route that runs through it, ending in Santiago de Compostella – once the world’s third most visited pilgrimage destination after Jerusalem and Rome. In terms of geography and climate, with the Atlantic Ocean as its nearest neighbour in both the north and the west, Galicia couldn’t be farther from what we tend to see as typically Spanish – the Mediterranean, sunlight, and palm beaches. This difference is neatly illustrated by the regional tourist board’s logo: the silhouette of a Catholic priest with an umbrella battling against strong headwinds.

Galicians also feel they are different. Their regional identity is strong and their language, Galego, is closer to Portuguese than Castilian, the majority language of Spain. The region boasts a rich literary heritage dating back to the Middle Ages that is currently enjoying a renaissance.

The region was colonised by Celts in around 500 bce. The Celts’ dominance lasted for close to 400 years, until the Romans conquered the area in 137 bce. In around 400 ce, the West-Germanic Suebi invaded, after which a brief Moorish interlude ensued before the region became part of the kingdom of Asturias. But the ancient stone monuments known as dolmens still stand as a reminder of the Celts’ presence. That’s probably why many Galicians flirt with the idea that they are actually a little bit Celtic, even though their DNA probably tells a very different story and Celtic languages haven’t been spoken in the region for some two thousand years.

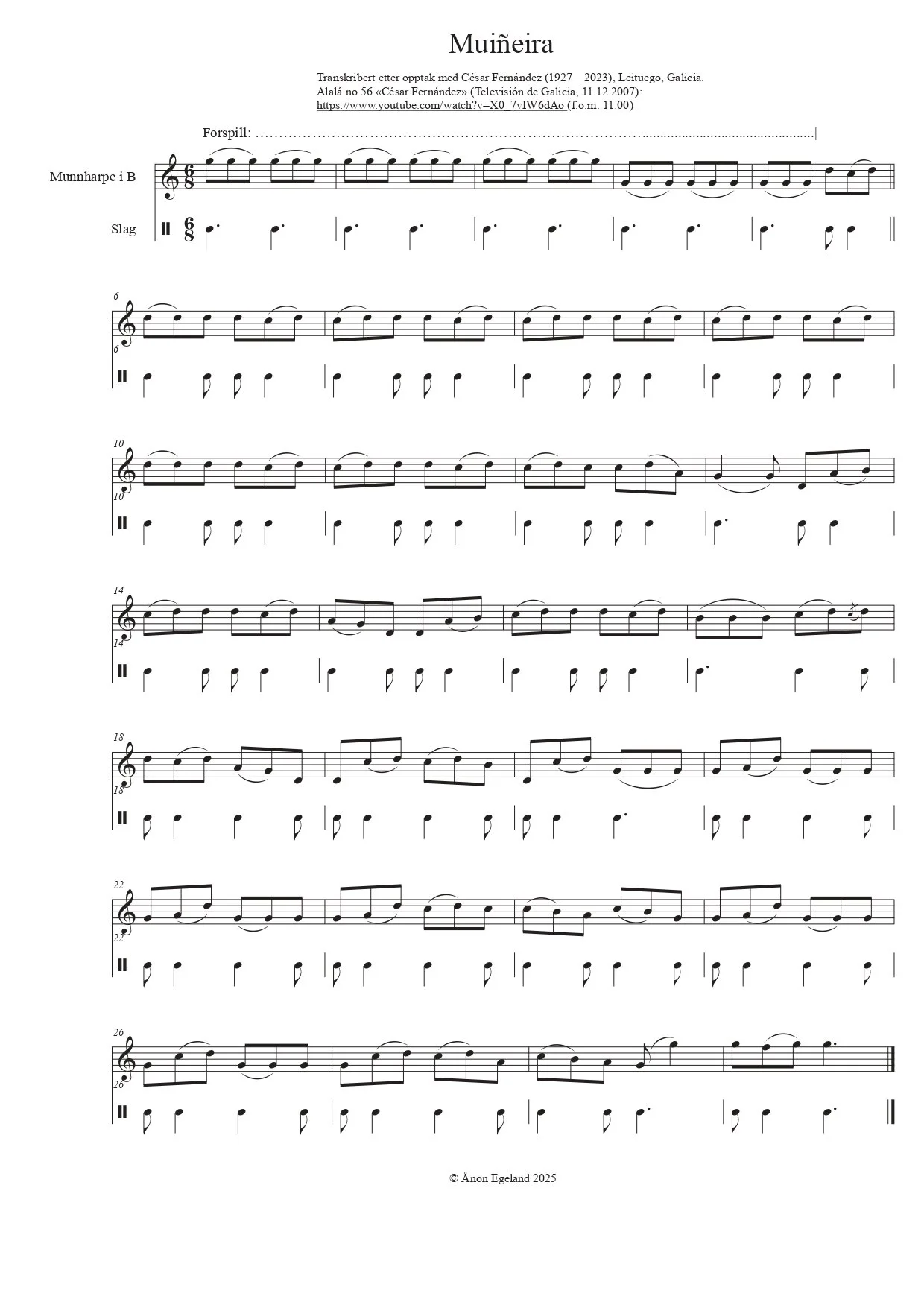

These kinds of romantic ideas are further fed by the region’s traditional music, where the plucked string instruments that dominate the rest of the Iberian Peninsula are notable for their absence. Here, Galician bagpipes, or gaita, dominate, along with various drums and tambourines. Even though today’s traditional dances, music and bagpipes are no more than a thousand years or so old – and therefore unconnected to the Celtic presence in the region – I accept that one of the most important and characteristic Galician dance types, the muiñeira, shares some of the rhythmical features of Scottish and Irish jigs. Yet one could say the same of the southern Italian tarantella…

The Jew’s harp – known as trompa or birimbao in Galician – also has its place among these traditional Galician instruments, and has enjoyed a major resurgence over the past few decades – in both makers and performers. In March 2003, I was lucky enough to experience this close up during the Xornadas de birimbao festival – Jew’s Harp Days – in the ancient city of Lugo. Celebrated guests like England’s John Wright and the Italian player Fabio Tricomi gave great performances, and I also had an opportunity to hear one of the key older Jew’s harp tradition bearers, César Fernández (1927–2023) – a lively chap then in his late seventies who didn’t let language barriers get in the way of communication. You can see and hear him play in several of the video links below.

Instrument-maker and multi-instrumentalist Sverre Jensen was a member of the Norwegian delegation; his fluent Spanish and impressive network of instrument-makers and players was crucial for a good professional exchange and for communication in a local milieu where Spanish rather than English tended to be the second language.

Galicia is one of the few areas in Europe that has, like Norway, a virtually unbroken tradition of forging Jew’s harps individually, rather than via a small-scale assembly line process. What’s more, to the best of my knowledge, Galicia is the only place in the world where the Jew’s harp tongue is fixed with a wedge apart from Setesdal, Telemark and Valdres in southern Norway. Archaeological finds from Belgium and Estonia, among other places, have revealed that this is a far from novel phenomenon, and that this method used to be more widespread than it is today.

In 2003, Galician knowledge of how to forge Jew’s harp, and in particular the crucial detail of fixing the lamella, was in such a precarious state that outside assistance was sought. The obvious man for the job was Folke Nesland, who held forging workshops over several days – in an old morgue! A suitably large and interested group took the workshop and, judging by the healthy state of the Galician Jew’s harp some twenty years on, it looks as if Folke Nesland did a great job. At any rate, I note that Jew’s harps forged by ‘Master Che’ (‘Che da Luaña’, Xosé Vásquez) are available on social media, and the local TV stations’ coverage of traditional music is exemplary.

Check out the videos here:

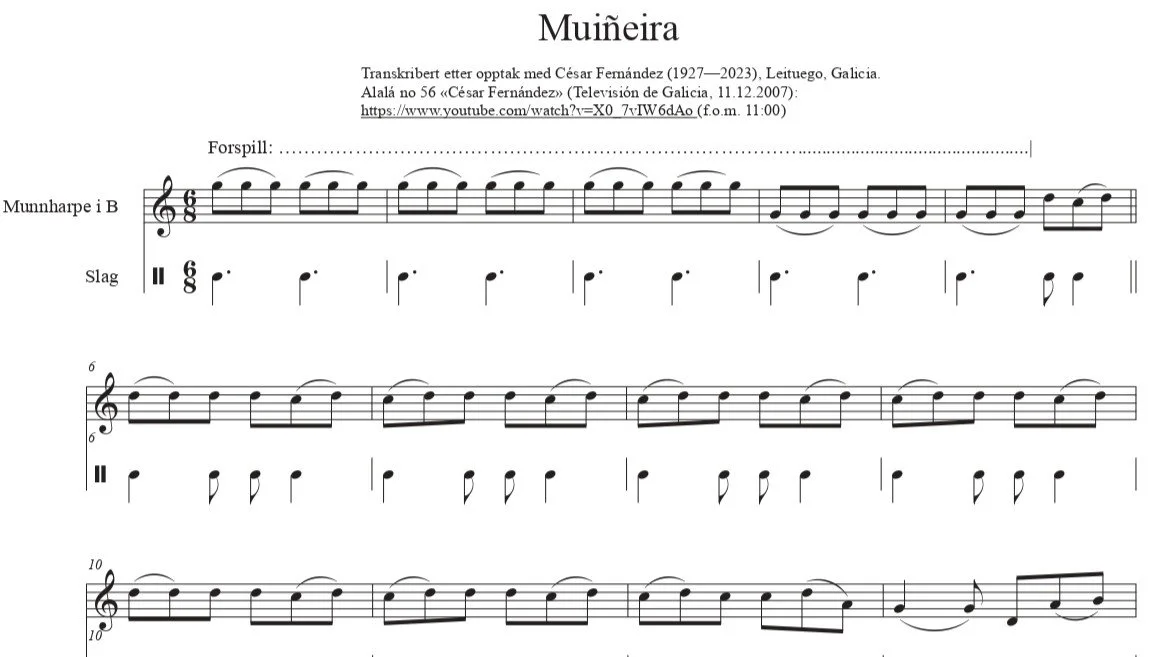

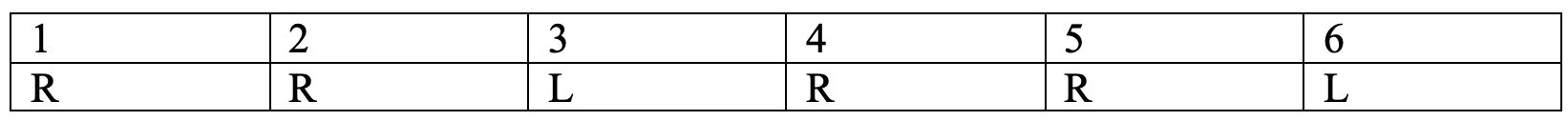

Like almost all other European Jew’s harp performance, the traditional Galician playing style is melodic. There is also a solid rhythmical underlay in the form of steady, fixed stroke patterns (or striking formulas as Dr. Andres Røine calls them) – just like in the Scots style described in previous Munnharpa articles. The earliest named muiñeira is a good example: the time signature is 6/8 (i.e. three equal-length notes per beat) and the underlying rhythm – which César Fernández demonstrated by holding a coin in either hand and tapping them against a bar counter – can be presented as follows:

R = right hand

L = left hand

Switch if you are left-handed!

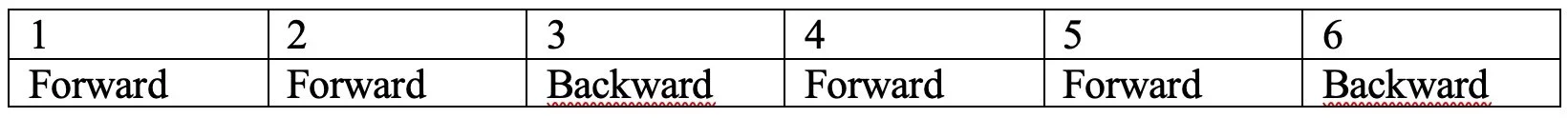

That’s the same rhythm Emilio do Pando plays when he accompanies the Jew’s harp playing of his nephew Daniel do Pando – using walnuts (!). He holds a whole nut against the right-hand corner of his slightly open mouth with his left hand, and strikes it with one half of an empty walnut shell: two strokes forward and one stroke backward, as below:

The end of each part is marked with two forward strokes on the first and fourth quaver. A typical phrase can therefore consist of seven measures that use the above pattern, followed by two strokes on the first and fourth quaver in measure eight.

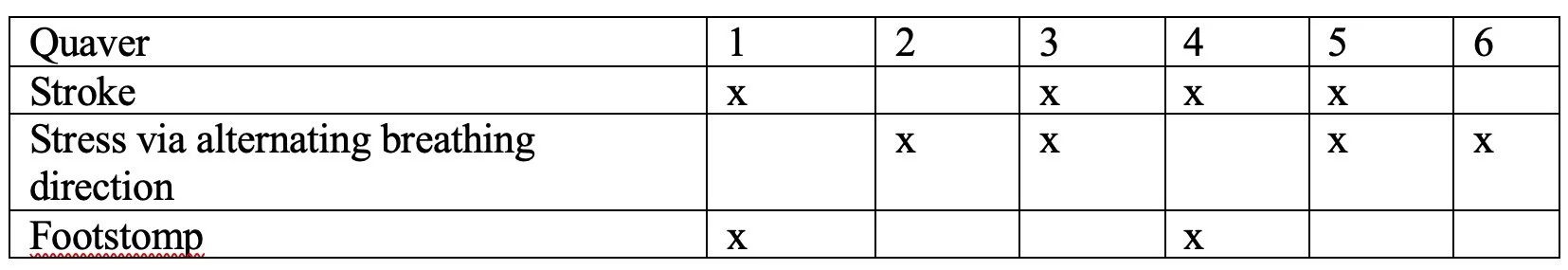

Things get more complex on the Jew’s harp. The rhythmical pattern struck by the hand varies somewhat, and the player’s breathing is also an important rhythmical tool in this style – as is evident in this recording of César Fernández (from 11:00).

The breathing is what creates the pulsation that is so audible in the introduction. The even strokes are followed by the foot-stomp, but you can still hear the three subdivisions clearly. As I perceive it, the stress on the first quaver comes from the stroke itself, while the stress on the two subsequent quavers comes from the alternating breathing directions. It’s hard to say whether the stress on the quavers after each beat is best played on an inbreath followed by an outbreath, or vice versa. At any rate, it makes most sense to change your breathing direction according to a fixed pattern. This is something you’ll probably have to figure out for yourself by trial and error. And remember that YouTube has a function that lets you slow down the speed of the recording!

To put it another way:

The stroke patterns can be understood as long–short, short–long, or one–two–three–four–five–six. (Count evenly to six and strike on the counting units in bold type.) The breathing stress goes: one–two–three–four–five–six. Variations in the stroke pattern are as shown in the following transcription. Measures 6–17 follow the above pattern, but then switch to short–long, long–short, or one–two–three–four–five–six. With the exception of the introduction and the very last notes, the melody remains firmly within the compass of a fifth, i.e. between overtones 8 and 12.

Knowing as I do that there is an element of what we might call cultural expectation in the way we interpret Jew’s harp melodies, I can’t guarantee that the melody I’m hearing is roughly the same as the one César Fernández had in his head when he recorded the tune in 2007. But I’ve done my best!

Good luck!